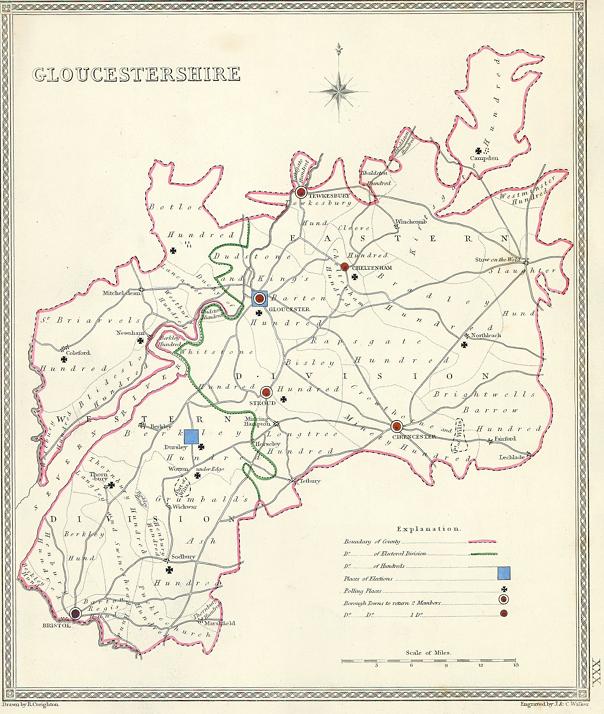

Electoral Districts, Gloucestershire, 1835. From Samuel Lewis, Topographical Dictionary of England, 1835. (www.ancestryimages.com)

The parliamentary constituency of West Gloucestershire had been created by the Great Reform Act of 1832. The constituency was represented by two members of parliament. In 1867, the West Gloucestershire representatives were Sir John Rolt, a Conservative, and Robert Kingscote, a Liberal. In that year, Sir John Rolt gave up his seat when he became a judge, so a by-election was declared. The Liberal candidate for the vacant seat was quickly announced as Mr Charles Paget Fitzharding Berkeley, second son of Lord Fitzharding of Berkeley Castle. The Conservatives took a long time in declaring their candidate. It had been expected that Sir George Jenkinson, 11th Baronet of Walcot and Hawkesbury, would be nominated. Sir George lived at Eastwood House, in Falfield, Gloucestershire, and he had been the High Sheriff of Gloucestershire in 1862. However, for reasons not made public, the eventual Conservative candidate was Colonel Edward Arthur Somerset, a cousin of the Duke of Beaufort.

The market town of Dursley was the place where the hustings for West Gloucestershire elections took place. On 31 July 1867, the candidates, their supporters and crowds of people gathered to hear the declaration of the results. Sir George Jenkinson came to Dursley to support Somerset on the hustings, bringing with him his wife and children, and other guests, including the Honorable George Charles Grantley Fitzharding Berkeley, commonly known as Grantley Berkeley. Grantley Berkeley was the uncle of Charles Berkeley, the Liberal candidate, but he had not come to support his nephew. Despite having been a Liberal MP in the same seat from 1837 to 1857, he was now supporting the Conservative candidate, Colonel Somerset. His appearance on the hustings alongside Somerset and Sir George Jenkinson led to hissing and cries of ‘turncoat!’ from Liberal supporters, who made up the majority of the crowd. The Gloucester Journal reported that the proceedings were very disorderly, and the presence of Grantley Berkeley appeared to be the principal cause of the unrest, coupled with the officiousness of Sir George Jenkinson, who ‘made himself conspicuous by obtruding himself on the notice of those assembled, bandying words with the crowd, and gesturing like a Merry Andrew’.*

When the High Sheriff declared that the Conservative candidate had won the election by 96 votes, there were cheers from the Conservative supporters, and jeers and cries of ‘bribery’ from the Liberals. Somerset gave a speech, and there was uproar when he thanked Sir George Jenkinson. In his speech, Charles Berkeley, the losing candidate, congratulated Colonel Somerset, then made a pointed reference to people who had promised to support him but then hadn’t done so. Grantley Berkeley tried to reply, but his voice was drowned out by booing, and then fighting broke out in the crowd. Grantley Berkeley persisted in trying to speak, shouting that the troublemakers were ‘no more fit to enjoy the franchise than a pack of wild beasts’. He continued to shout at the top of his voice while the crowd booed, but when sticks began to be thrown, he retreated from the hustings. Jenkinson remained for a while longer, berating and taunting the spectators.

A little while later, Sir George Jenkinson decided it was time to leave Dursley. As he and his family got into their carriage, they were heckled and missiles were thrown at them. The police surrounded the carriage as its occupants were pelted with rotten eggs, offal, horse-dung, turf and sticks, and a sheep’s head was thrown repeatedly back and forth over their heads.

Following this riotous behaviour, five people were arrested and appeared at a special Petty Sessions which was held at Dursley on 10 August. The Gloucester Journal reported that the proceedings “created a great deal of excitement in Dursley, and the court was thronged”. There were six magistrates on the bench and the hearing lasted eight hours. A large number of constables were present in the town, in case of any further disturbances. Gloucester solicitor Mr Taynton represented the prosecutors, while Mr Gaisford of Berkeley appeared for the defendants.

Henry Woodward, Andrew Kilmister, William Dean and Richard Lacy, along with Rowland Hill, described as “a boy”, were charged by Superintendent Griffin of the Gloucestershire Constabulary, that they did, “with divers other evil-disposed persons, to the number of ten or more, on the 31st July 1867, at the parish of Dursley, in the county of Gloucester, unlawfully and riotously assemble and gather together to disturb the peace of our Lady the Queen, and that, being then and there so assembled and gathered together, they did unlawfully and riotously make an assault upon one Sir George Jenkinson, Bart, and the Hon. G.F. Berkeley, and others, to the great disturbances and terror of the liege subjects of her Majesty the Queen then and there being”.

Mr Taynton stated that he had been instructed to prosecute by the Chief Constable of the Gloucestershire Police, who wanted brought to justice all the persons who could be proved to have taken part in this “very scandalous outrage”. The magistrates might decide the defendants had not been guilty of committing a riot, but he prayed that in that case they would be sent for trial on charges of tumultuous and unlawful assembly.

Police Sergeant Monk of Dursley was the first witness. He had been on duty on 31 July, the day when the High Sheriff officially declared the result of the poll in the recent election. There were about four hundred to five hundred people assembled near the Bell and Castle Inn, and their conduct had been riotous and noisy. Monk saw Sir George Jenkinson’s carriage being brought out from the yard of the Bell and Castle Inn, when it was time for him to leave. Sir George came through the crowd with some ladies towards the carriage. He was struck on the back by an egg. As the party got into the carriage, more eggs were thrown. The police surrounded the carriage to protect the occupants. He saw a sheep’s head being passed over the carriage, but he did not see any missiles hit anyone in the carriage. The eggs passed over the ladies’ heads, but one struck the back of the box were Sir George was seated. He had heard the name “Grantley” uttered most by the crowd. Monk identified Henry Woodward and Andrew Kilmister as part of the mob. When the carriage left, it had been followed by the crowd for a few hundred yards, who threw stones and anything else they could find. The crowd dispersed once the carriage had gone.

Captain Kennedy, C.B. (a former governor of Vancouver Island) was another witness. He had been one of Sir George Jenkinson’s party. He had seen stones, eggs, sticks, bones and offal being thrown at the occupants of the carriage. He had caught Lacey with a bag of eggs, and handed him over to the police. Lady Jenkinson and Miss Jenkinson had blood on their faces. The former lady’s face was cut, but the blood on Miss Jenkinson’s face was from being struck by a piece of offal. Kennedy’s wife had been hit by two apples.

Police Constable Gough stated that he had seen Rowland Hill, the boy, pick up the sheep’s head and throw it at the carriage. He also saw William Dean in the crowd, shouting and pushing. Another constable identified Henry Woodward as being the chief culprit. He had seen the other defendants in the crowd, but hadn’t witnessed them doing anything. Woodward had thrown things at the carriages of Sir George Jenkinson and Colonel Somerset.

Having heard all the evidence, the magistrates declared that “a most disgraceful riot” had been committed, and all the defendants except William Dean were committed for trial at the next county Assizes.

After this, Sir George Jenkinson appeared to answer a charge that on the day of the election, he assaulted one Thomas Ward, by striking him with his whip as he drove past him, on his way into Dursley. Sir George was hissed as he entered the courtroom. Ward, described as a labourer and a corporal in the Militia, stated that on 31 July, he was standing at the Kingshill turnpike with others, dressed in yellow, the colour of the Liberal supporters. As Sir George Jenkinson drove his carriage past at a trot, he stood up and brought his whip down on him. He would have been cut across the face if he hadn’t managed to turn his back.

Another witness said that the crowd standing at the turnpike had not been hostile, and only shouted “Yellow forever” as each carriage drove past. There was also a suggestion from Mr Gaisford that Sir George had, in a vulgar gesture, lifted his coat-tails and slapped his “nether-ends” in the direction of the crowd. In his defence, Sir George said that the crowd at the turnpike had rushed his carriage and frightened the horses. He said that Ward had confronted him in an inn at Dursley and demanded money, or else he would accuse him of assault. The bench decided to fine Sir George Jenkinson 40 shillings for assaulting Ward.

The four defendants who were sent for trial on charges of rioting did not have to wait long for their case to be heard, as the Gloucestershire Assizes began soon afterwards. The charge against them was of riotous assembly and assault against Sir George Jenkinson, Bart, the Hon. Grantley Berkeley, and others. The judge, Mr Shee, in his opening statement, suggested that if the committing magistrates had been afforded more time to reflect, they might have decided that it would have been better to fine the defendants, rather than having them sent for trial at the Assizes.

Opening the prosecution case, it was submitted that the assault on Sir George and his party had been premeditated, because rotten eggs in brown paper bags had been brought in to Dursley from elsewhere. The evidence given at the Dursley Petty Sessions was then repeated. After hearing the case against Rowland Hill (who was about thirteen years old), the prosecution withdrew the charge against him, because he was “only a boy”. The judge said the boy should never have appeared in the dock at all.

Sir George Jenkinson, Lady Jenkinson and their eldest daughter, Miss Emily Frances Jenkinson, all appeared as witnesses. Lady Jenkinson stated that she had been hit on the temple by a hard green apple, which caused severe bruising. Her daughter Emily had been struck several times by stones and offal, and her little boy had been cut below one of his eyes and was still in bed recovering.

Sir George Jenkinson was given a thorough grilling by the defence counsel, Mr James. He denied having enraged the crowd, said he didn’t recall hitting Ward with his whip, but did admit that he had tried to hit someone else, but had missed. He emphatically denied having lifted up his coat tails and slapped his bottom, in a vulgar gesture. Several Dursley residents appeared to give good character references to the defendants. In his summing up, Mr James castigated Jenkinson, as the prosecutor of the case, for allowing Rowland Hill, a child, to be held in custody for six days and nights before the trial. He also criticised him for taking ladies and children to the election hustings, when he knew such occasions were always rowdy. James was applauded when he sat down.

After consulting together for three minutes, the jury found the remaining defendants not guilty. The trial had lasted nearly five hours.

Detail from “An Election Squib” by George Cruickshank, 1841 (www.ancestryimages.com)

A note on Sir George Jenkinson

Sir George Samuel Jenkinson was the 11th Baronet of Walcot, Oxfordshire and Hawkesbury, Gloucestershire. He was the son of the Bishop of St David’s and a first cousin once removed of one-time Prime Minister Robert Jenkinson, 2nd Earl of Liverpool. He had succeeded his uncle as Baronet in 1855. He had been the High Sheriff of Gloucestershire in 1862. He unsuccessfully contested the seat for Wiltshire North in 1865 and of Nottingham in 1866. During these election campaigns, he had gained a reputation for being boastful and bumptious, but was said to be popular with landed proprietors and tenant farmers. In 1868, he finally succeeded in becoming a member of parliament, being elected as the representative for Wiltshire North. He stayed in that seat until 1880. He died at his home, Eastwood House in Falfield, on 19 January 1892, and was buried in Falfield Parish Church.

Although his behaviour at the Dursley election caused him to be viewed as an arrogant “toff”, his obituary in the Gloucestershire Chronicle on 23 January 1892 showed a different side to his character. On succeeding to the Eastwood Estates, it said, he had built the present church, vicarage and schools in Falfield, almost entirely at his own expense. He was ‘of a most liberal and generous disposition’, and supported all the local institutions, was generous to the poor and was a large employer of local labour, who was ‘widely and deservedly respected’. Perhaps the passing of twenty-five years had mellowed his character.

*I have no idea what this means.

Sources

Dictionary of National Biography

Cheltenham Looker-On, 12 Jan 1867

Gloucester Journal, 27 July, 3 August, 10 August, 17 August 1867

Gloucestershire Chronicle, 23 January 1892

© Jill Evans 2017