This is a story about two women living in Cheltenham in the late 1820s, who had very different experiences at the hands of the local police and magistrates when they were accused of theft. One woman was Ann Hammerton, a milliner and dress-maker, in her late twenties, attractive, charming and eloquent. The other was Mary Davis, middle-aged, never married, a former housekeeper to Sir Arthur and Lady Faulkner, and in receipt of a small annuity from a nephew.

The two women had become acquainted and although Mary Davis was supposedly less well off than Ann Hammerton, she had loaned some money to the younger woman. Hammerton had not been able to pay her back and in October 1827 she invited Davis to come and live with her at her home in Albion Street, rent free, as a means of repaying the debt. The women shared a bedroom and the kitchen and parlour. There were two other lodgers living in the house.

Mary Davis received an annuity of £20, which was paid to her in two parts. On 15 November 1827, she received a letter from her nephew, who lived in Wales, containing a part payment in the form of a £10 Bank of England note. The following evening, the two women took tea together in the kitchen and chatted for some time, until eventually Hammerton went upstairs to their bedroom. Soon afterwards she called out that they had been robbed. In the bedroom, a pillow was hanging out of the window and other bedding was lying in the back yard. Mary Davis found that her trunk, contained the ten pound note and most of her clothes, was missing. Ann Hammerton said she had lost items too.

Another lodger returned to the house with her brother just after the robbery was discovered. The brother went outside and although the ground was wet, he could find no traces of anyone having been in the yard. It was a strong possibility that this may have been an inside job, disguised to look like a break-in. The police were fetched, but there was no clear evidence as to who was responsible.

Although several people had been suspected of the theft, including another lodger, a tailor, who had given up his rooms shortly after the incident, Mary Davis had not considered that Ann Hammerton might have been involved, until one day by chance she found some of her missing items amongst Hammerton’s belongings. After this discovery, Davis left the house in Albion Street and went to lodge elsewhere. She did not inform the police of her suspicions immediately, perhaps preferring to end her friendship with Hammerton and not get the authorities involved.

Not long after moving into her new lodgings, a parcel was delivered to her which contained some of her stolen items. An anonymous note came in the parcel, urging her to search the houses of certain people and to visit a ‘cunning man’ to help her identify the thieves. Davis did visit such a man twice. On her first visit, he told her that two women were behind the theft, and the description of one of them was very like Ann Hammerton. On the second visit, he told Davis that it was unlikely that she would ever recover her missing money.

On 5 January 1828, Mary Davis went to the Cheltenham Police Office and made a complaint against Ann Hammerton. On the following day, Hammerton was brought before the Cheltenham magistrate Robert Capper. He ordered her to return three days later, after more inquiries had been made. He did not remand her in custody during the time between the appearances. When Ann Hammerton returned to the police court on 8 January, Capper released her without charge.

A few weeks after Hammerton was released, she went to the police office and spoke to George Russell, who was the High Constable of Cheltenham and the chief of the town’s police. She had with her a letter, which was addressed to Mary Davis and had been sent to Hammerton’s house. She said she had ‘peeped’ into the letter and its contents made her suspect that Davis herself was involved in the robbery. The letter, which was badly written and poorly spelt, made some vague references to the robbery and was signed ‘Obadiah’. On the grounds that this letter was from an accomplice, Russell went to Davis’s new lodgings, at about 11 o’clock at night on the 28 January, and took her into custody. She was walked to the Cheltenham police lock-up, where she was kept overnight.

On the next day, Mary Davis appeared before the magistrate Robert Capper. He asked her who had written the letter and she replied that she had no idea as she had never seen it. She also said she didn’t know who ‘Obadiah’ might be. Capper said she would be sent to Northleach House of Correction for fifteen days, for further examination. At the end of that time, she had to wait another three days in prison until Mr Capper, as the magistrate who had committed her, was present on the bench. He then told her that no further evidence had been found against her and she was free to go.

At this point, Davis tried to present fresh charges against Hammerton, but Capper refused to hear them. However, the matter was sent to counsel for consideration and it was determined that there was a case to answer against Hammerton. On 17 March 1828, the Cheltenham Journal reported that Ann Hammerton had been bailed to appear at the next Assizes to answer any bill of indictment which might be preferred against her by Miss Davis. The report added, ‘The Prosecutrix had lately been in custody on a charge of felony preferred against her by Miss Hammerton – quid pro quo.’ The magistrate Ann Hammerton appeared before was – who else – Robert Capper.

Ann Hammerton was tried at the Gloucestershire Spring Assizes, surrendering to take her trial on 8 April. Being of a somewhat different appearance to the usual prisoners who appeared in the courtroom at Gloucester’s Shire Hall, she excited some interest. The Cheltenham Chronicle (12 April 1828) reported that Hammerton was ‘not handsome, but with quick intelligent dark eyes, a genteel appearance, and being well dressed, her tout ensemble was extremely interesting’. She pleaded Not Guilty to the charges made against her in a firm voice.

The prosecution detailed the events which had led to this point, and contended that the prisoner had kept Davis occupied in the kitchen while an accomplice robbed the house. She was further accused of writing the letter included in the parcel Davis had received, and the letter supposedly from Davis’s ‘accomplice’. She had also written to Davis’s nephew, begging him to state that his aunt was not in her right mind. Another crucial fact in the evidence against her was that after the robbery, Mary Davis had obtained from her nephew the serial number of the bank note he had sent her, so she could alert the banks not to accept it. Hammerton had offered to go round the local banks for Davis to give them notice that the bank note was to be stopped, and after being out for a few hours, she had returned home and said she had completed this task, but it was now known that she had not done as she said.

After hearing all the evidence from the prosecution, Hammerton was invited to speak in her own defence, and she gave a long speech with great confidence. However, the jury did not take long to find her guilty and the judge, Mr Baron Vaughan, said he would sentence her to the maximum punishment allowed for such a crime as this, which was to be transported for seven years. She appeared to receive her sentence with great composure.

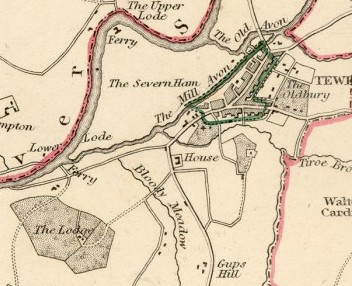

On the morning after her trial, the matron took Hammerton’s breakfast into her cell and told her that after she had eaten and dressed, she would be transferred from the gaol to the penitentiary. When the matron went back later, she found that Hammerton was dead, having managed to strangle herself with a silk handkerchief attached to a window bar. An inquest was held and the jury found that Ann Hammerton had been temporarily insane when she took her own life, which meant she could be buried in consecrated ground. She was said to come from a respectable family in Tewkesbury, and her burial took place there on 11 April 1828.

This case had come to a sad end. It seems quite likely that Ann Hammerton, with her eloquence and good looks, might eventually have made a success of her enforced move to Australia, if she had lived. As for Mary Davis, she had been vindicated, but she was not at all happy. She must have been deeply shocked by the death of her former friend, but more than anything, she was finding it difficult to recover from the treatment she had received at the hands of the Cheltenham police and magistrates. In August 1828, two actions were presented in the Civil Court of the Gloucestershire Assizes, in which Mary Davis was the plaintiff.

Davis v Russell et al.

In the first case, Davis (the plaintiff) accused George Russell (the defendant) and other police with false imprisonment. The counsel for the plaintiff, Mr Curwood, said this case was ‘more singular than he had ever met with in his long experience’. Davis was, he said, ‘a female advanced beyond the middle period of life’, and had been housekeeper to Sir Arthur and Lady Faulkner. In that situation she had conducted herself in such a way that Lady Faulkner had an extremely high opinion of her.

Curwood then outlined the details of the case and came to the crucial evidence as far as this action was concerned, which was that Ann Hammerton, after first being accused of committing the crime herself, had written a letter in a feigned name, which imputed that Miss Davis had been guilty of the robbery with an accomplice. When Hammerton took this letter to Mr Russell, he, without a warrant, went to the lodgings of the plaintiff, on a Sunday at about 11pm, and took her away to prison, where he kept her till the next day. Curwood asked for damages to be awarded to Davis for this violation of her liberty.

Miss Mary Ann Hall was called to give evidence. She lived with her father in Malvern Place, Cheltenham, where Miss Davis had taken up lodgings after leaving Ann Hammerton’s place. Between 10 and 11 o’clock at night, the witness and her sister were getting ready for bed when there was a violent knocking on the front door. Miss Davis was already in bed. The door was not opened straight away and somebody outside called out that if it was not opened, it would be broken down. Miss Hall and her sister stayed in their room and from there she heard Miss Davis ask what was the matter and Russell said to her, “Some of your villainy is come out.” Davis asked repeatedly what was the matter but they would not tell her. They took her out of the house to the prison.

Mr Collier, attorney for the plaintiff, said he had been at Ann Hammerton’s trial, before Mr Baron Vaughan. He heard Russell examined as a witness. The judge said to Russell, “I hope you had a warrant for all this you did to Miss Davis”. Russell said he had not, for he thought the end justified the means.

Mr Taunton, counsel for the defendants, said the question was whether the constables had fair and reasonable grounds for suspecting that Miss Davis had been concerned in the robbery. If constables and magistrates were not protected from actions for damages such as this, it would cripple the effect of the laws and impede the administration of justice.

Mr Curwood contended that there was nothing in the information Russell had received which could in any way excuse the proceedings against Miss Davis, without the authority of a warrant; and it was evident the charge had been exhibited against Miss Davis, in order to get rid of the accusation which she had made against Miss Hammerton. He was sure therefore that the jury would award ample damages.

The presiding judge, Mr Justice Gaselee, in summing up, left it to the jury to determine whether there had not been such a reasonable cause on the part of the constable as would justify the course he had pursued, and which was not perfectly in conformity with the law. It was quite manifest that Miss Davis was an innocent person; but still, if the constables acted on fair grounds, they were justified in what they did. Verdict was given for the defendants.

Davis v Capper et al.

In the second case, heard the next day, Robert Capper, magistrate of Cheltenham, was the chief subject of Mary Davis’s complaint. The evidence of the previous case was largely repeated, but concentrated this time on Capper’s actions after Ann Hammerton accused Davis of being the thief. When Davis appeared before the magistrate on 29 January, he had asked her about the letter Hammerton had produced and wanted her to identify the author of it. When she could not give him a satisfactory answer, Capper committed her to Northleach for 15 days, “for further examination” and said she might remember who had written the letter in that time.

William Newton, the keeper of Northleach House of Correction, said in evidence that Mary Davis had been in the prison under the same conditions as someone committed for a misdemeanour. This meant she was given bread and water, but if she had money, she was free to buy more provisions, and extra coal for the fire. She had, in his opinion, been treated better than other prisoners in the same position as her.

Lady Faulkner, the wife of Sir Arthur Brooke Faulkner, MD, then appeared as a witness. She had previously employed Mary Davis as her housekeeper. She believed Davis was between 40 and 50 years of age. After she came out of prison, she had offered to re-employ her. She believed the experience of being held in prison had caused her suffering and afterwards she appeared distracted in her mind.

Mr Collier (the plaintiff’s attorney) was called and said he attended the police office on 16 February, when Mary Davis was discharged. Mr Capper said there was no evidence against Davis. He also stated that he had committed her for 15 days on the advice of Mr Griffiths, the Magistrate’s clerk, and that he did so in the hope that she would tell who wrote the intercepted letter.

Mr Taunton, appearing for Capper, said that how long a suspect was held for further examination was entirely up to the committing magistrate. He then contradicted this statement somewhat by saying that Capper had acted under the direction of the Magistrates’ Clerk. Mr Curwood, acting again for the plaintiff, argued that a commitment for re-examination for so long as 15 days was ‘illegal on the face of it’.

Mr Justice Gaselee said that on the best consideration he could give the case, this was not an illegal warrant. The Magistrate had power to commit for re-examination, but as the period for which he could do this was undefined, he thought it best to to let the case go to the jury. Unfortunately, after considering the case for the rest of the day and then returning to continue with their considerations the day after, the jury was unable to agree on a verdict. The judge decided there were no grounds to find for the plaintiff and the case was dismissed.

After the verdicts in both of these cases had been given, Sir Arthur Brooke Faulkner, Mary Davis’s former employer, wrote a very long letter to Robert Peel, then the Home Secretary, and had the letter published in the columns of the Cheltenham Chronicle (28 August 1828). Extracts from the letter also were printed in newspapers nationally. Sir Arthur said he had no complaint to make against Mr Russell or Mr Capper personally, but rather he blamed the state of the law, which placed too undefined a power in the hands of the police and the magistrates.

He did, however, express some surprise at the readiness of the police and the magistrates to believe that Mary Davis was the guilty party in the case, saying that her treatment had rested on the evidence of ‘a person who had already been under a charge of the robbery in question’. He highlighted the manner in which ‘poor Davis’s looks were most unceremoniously dealt with; they were taken as a kind of prima facie evidence against her, and certainly age, wrinkles, and silence, arrayed against youth, beauty and persuasion…were fearful odds.’ However, he doubted there was ‘an honester countenance to be met with than that of poor Davis’, who had been ‘good-humoured, well-tempered and rather gay, until her late misfortunes’. It seemed to him that Mary Davis had been regarded as someone who could be treated in the way she had been because she was relatively poor and had been a servant, although she came from a respectable family. However, whatever her situation in life, she was as entitled to equal protection under the law as anyone else.

The collapse of the case against Robert Capper was not the end of the story, because the court of King’s Bench gave permission for Mary Davis to bring her case before the Gloucestershire Assizes again, having ruled that the judge in the first case had misdirected the jury.

Davis v Capper

In September 1829, the case of Davis v Capper was opened again on the civil side of the Gloucestershire Assizes, before Mr Baron Vaughan (the judge who had presided at the trial of Ann Hammerton in April 1828). The case was heard over two days and was reported in both the local and national newspapers. Much of the detail was the same as in the original case, but there was some interesting new information concerning the actions and motives of Robert Capper.

Going back to the original accusation which Mary Davis had made against Ann Hammerton, the plaintiff’s counsel (who again was Mr Curwood), stated that Hammerton had appeared before Mr Capper on 5 January and was told to return three days later. On the evening before she was due to reappear, Hammerton had a private interview with Capper, which lasted about an hour. The next day, when she appeared before him, Capper discharged her, without taking any sureties for her further appearance.

In contrast, Mary Davis, described as ‘a woman advanced in years’, had been taken up on a charge of committing the same felony. At the examination which took place before Robert Capper, no proof was offered of her guilt and the articles which were said to have been stolen by her had not been found in her possession, but her accuser had produced a letter addressed to Davis, which she said she had intercepted. On the evidence of this letter, Davis was committed to Northleach House of Correction for 15 days, for further examination. At the end of that time, she had to wait for another three days in gaol, until Mr Capper was available to take his place on the magistrates’ bench. It was suggested that ‘Mr Capper, in the discharge of his duty, let go the young and handsome Miss Hammerton, who was afterwards convicted on the very evidence he rejected, and he committed the old, the helpless, and the innocent Miss Davis, to compel her to give evidence against herself.’

Speaking of the former civil case brought against Capper, Mr Curwood said that it had been agreed then that if the defendant had assumed to himself an excessive jurisdiction, he was liable for the consequences. He would state with confidence, that Mr Capper was not authorized to commit for such a length of time; if he acted illegally, whether or not he acted bona fide [in good faith], he was answerable for the trespass. He then proceeded to remark on the circumstance of the defendant, as it was alleged, having committed the plaintiff to prison, with a view to extort from her a confession – a proceeding which, he contended, was ‘contrary to every principle of British jurisprudence’.

Mr Collier, Mary Davis’s attorney, was called to give evidence. He stated that he had first attended Mary Davis as her legal representative when she appeared before the magistrates after her period in gaol. He had spoken to Mr Capper before Davis’s appearance that day. Capper had said that after discharging Ann Hammerton on 8 January 1828, the police had been trying to find the ‘conjurer’ Mary Davis had consulted, as his was the only evidence that made Davis suspect Hammerton. (He appeared to have forgotten Davis finding some of her missing items among Hammerton’s belongings.) During his private interview with Miss Hammerton on 7 January, she had told him that Davis kept bad company and was always speaking ill of the parish minister, Mr Francis Close. He had also learnt from making inquiries that Miss Hammerton was a very religious person.

Collier said that after Mary Davis was discharged, he had made a charge against Miss Hammerton and said he had depositions from more witnesses, plus one witness who had come to court now. This witness said she had seen a petticoat which she knew belonged to Davis lying on Ann Hammerton’s sofa. Collier said Miss Hammerton seemed ‘very much confused’ by this statement. Mr Capper said it was a very mysterious business and he would have nothing more to do with it. Collier went to see Mr Capper again on 14 March, but again he refused to interfere.

Cross-examined by the counsel for the defence, Mr Taunton, Collier denied that he had persuaded Mary Davis to pursue this case because she was having difficulty paying for his services and he hoped to recoup his money if his client was awarded damages. Questioned about Mr Capper’s motives concerning Ann Hammerton, Collier said he did not believe that the magistrate had been fascinated by her, but he did think he had acted very partially. A question also was raised concerning whether Mr Capper had told Davis that the period of 15 days had been decided upon because the anonymous letter had said the writer would send another missive in two weeks. Collier said no mention was made of this at the time.

After all the evidence for the prosecution had been heard, Mr Taunton addressed the jury. He said he had the great honour to appear for the defendant, as he knew it was common opinion that ‘a more honourable, a more upright, or a more well-meaning man than Mr Capper did not exist’.

The Jury had heard it stated in the opening speech of his Learned Friend that the defendant had ‘been induced to prostitute himself’ for purposes of partiality, because Ann Hammerton was a fascinating, beautiful young woman, and Mary Davis a poor and wretched old one. He asserted that there was no proof that Capper had acted incautiously or injudiciously, the only question being over the length of the period for which the plaintiff was committed.

Regarding the anonymous letter, Taunton said the jury should not consider it in the light in which it now stood, when information had been obtained as to its being a spurious composition, but they should ascertain the effect that such a production would be likely to make at the time it was used. The magistrates had been induced to believe that the letter had been written by an accomplice of Davis, and she was then charged with theft. Taunton then stated that the letter alluded to another one being written at the end of 14 days, and it was with a view to obtaining a clue as to the writer of that letter that Davis had been committed for the length of time she had been. He believed Capper would be found to have acted with sound discretion.

Regarding Mr Capper’s refusal to look at the new depositions submitted against Ann Hammerton or to take any further action against her, Capper had said that there were some important facts omitted from the depositions and he had asked the clerk and constable how he should proceed.

Mr Baron Vaughan said the question here was whether Mr Capper had exceeded his jurisdiction, for if he had, he was answerable in this action, and that the question would involve two points, which were – was this a commitment not made bona fide, but tainted with some sinister motive, such as the hope of extorting a confession? Or was it, without being made for a corrupt motive, a commitment for an unreasonable time? In either of these cases it would be illegal. A magistrate had the power to commit for further examination, but that could only be for a reasonable time; and upon the question of what was a reasonable time, he would say that must depend upon the circumstances of each particular case. In his judgement, the amount of time for which the plaintiff had been held was unreasonable, unless there had been circumstances to account for it, and those circumstances it would be incumbent on the magistrate to show. In this case, all that was shown was that a woman, Hammerton, made an accusation, unsupported by any corroboration except a letter which never reached the hands of the plaintiff. He left it to the jury to say whether the commitment was made bona fide, or with a sinister motive, and if it was bona fide, whether it was a reasonable length of time. His Lordship gave it as his opinion that this commitment by Mr Capper was illegal.

The jury retired for about an hour, and then returned a written verdict that – ‘We consider that Mr Capper has acted bona fide, and without any impure motives, in the committal of Mary Davis for re-examination. We consider the period of committal unreasonable. We find for the plaintiff – Damages £10.’

The case of Davis against Capper was still not over, however. In November 1829, Capper’s attorney Mr Taunton brought the case before the King’s Bench in London. He complained that the damages awarded to Miss Davis should not stand, because the jury’s verdict had been that the magistrate had acted bona fide. The court stated that it would need time to consider. A week later, it was stated that the judges unanimously agreed that the verdict should stand. ‘A magistrate was not warranted in committing for re-examination for a longer period than was absolutely necessary, and in this case, the time…was outrageous and rendered the proceedings illegal ab initio. The plaintiff consequently had a clear case against the defendant and the Court would not disturb the verdict.’

It appears that this finally brought the matter of Mary Davis versus Robert Capper to a conclusion. It can only be hoped that the lady received her ten pounds promptly and that in time, she was able to recover some of her former good spirits.

Acknowledgement

I first came across this strange tale in the book, Murders & Misdemeanour in Gloucestershire, 1820-29, by Malcolm Hall (Amberley Publishing, 2008). The author concentrated on the trial of Ann Hammerton and the first civil case against George Russell. This led me to undertake further research into the story.

Sources

Newspapers (all accessed on British Newspaper Archive):

Bell’s Weekly Messenger, 6 September 1829

Cheltenham Chronicle, 17 April 1828, 28 Aug 1828, 3 Sep 1829, 12 Nov 1829

Cheltenham Journal, 25 August 1828, 7 September 1829

Law Chronicle, Commercial and Bankruptcy Register, 9 Oct 1828.

London Evening Standard, 2 September 1829

Morning Chronicle, 13 Nov 1829

Other sources (accessed on Ancestry.co.uk):

Gloucester County Prison, Register of Prisoners, 1825-29, entry for Ann Hammerton, 8 April 1828

Tewkesbury Parish Registers, Burials, 11 April 1828

© Jill Evans, 2024